Authored by By Yashvi Shah

McAfee Labs have identified an increase in Wextract.exe samples, that drop a malware payload at multiple stages.

Wextract.exe is a Windows executable file that is used to extract files from a cabinet (.cab) file. Cabinet files are compressed archives that are used to package and distribute software, drivers, and other files. It is a legitimate file that is part of the Windows operating system, and it is located in the System32 folder of the Windows directory. However, like other executable files, it can be vulnerable to exploitation by malicious actors who might use it as a disguise for malware.

Some common ways that malicious actors use a fake or modified version of wextract.exe include:

- Malware Distribution: Malicious actors can use a fake version of the wextract.exe to deliver malware onto a victim’s computer. They can disguise the malware as a legitimate file and use the fake wextract.exe to extract and execute the malicious code.

- Information stealing: A fake or modified wextract.exe can be used to steal sensitive information from a victim’s computer. Malicious actors can modify the code to include keyloggers or other data-stealing techniques.

- Remote Access: Malicious actors can use a fake wextract.exe to gain remote access to a victim’s computer. They can use the modified wextract.exe to create a backdoor or establish a remote connection to the victim’s computer, allowing them to carry out various malicious activities.

- Ransomware Delivery: Malicious actors can use a fake or modified “wextract.exe” to install ransomware on a victim’s system. For example, they may create a fake Windows Installer package that appears to be a legitimate software update or utility but also includes a modified “wextract.exe” that encrypts the victim’s files and demands a ransom payment for their decryption.

McAfee Labs collected malicious wextract.exe samples from the wild, and its behavior was analyzed.

This blog provides a detailed technical analysis of malicious “wextract.exe” that is used as a delivery mechanism for multiple types of malwares, including Amadey and Redline Stealer. It also provides detailed information on the techniques used by the malware to evade detection by security software and execute its payload. Once the malware payloads are executed on the system, they establish communication with a Command and Control (C2) server controlled by the attacker. This communication allows the attacker to exfiltrate data from the victim’s system, including sensitive information such as login credentials, financial data, and other personal information.

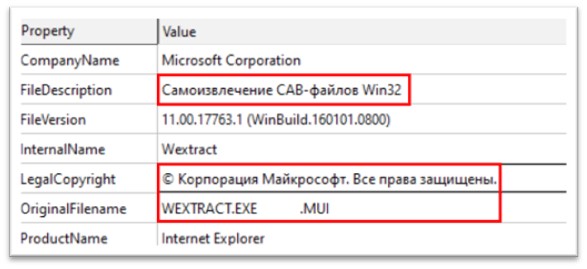

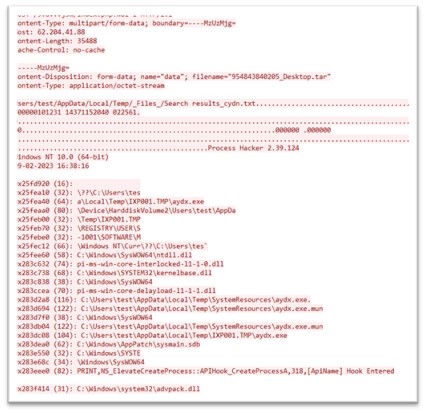

Figure 1: Characteristic of the file

The file is a 32-bit Portable Executable file, which is 631.50 Kb in size. The original name of the file is WEXTRACT.EXE.MUI. The file description is “Самоизвлечение CAB-файлов Win32”, written in Russian, and means “Self-Extracting Win32 CAB Files”. The legal copyright mentions Microsoft Corporation. A lot of static strings of this file were found to be written in Russian.

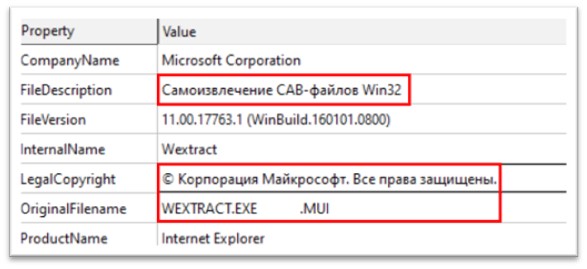

Normally, the resource section (.rsrc) contains resources used by the program, such as icons, bitmaps, strings, and dialog boxes. Attackers leverage the resource section of a PE file to improve the success of their attacks by evading detection, enhancing persistence, and adding functionality.

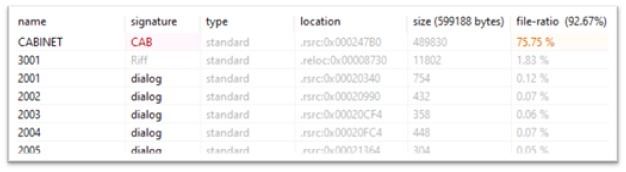

The resource section of this sample has multiples files, out of which CABINET resource holds 75.75% of the total file, which makes the said resource suspicious.

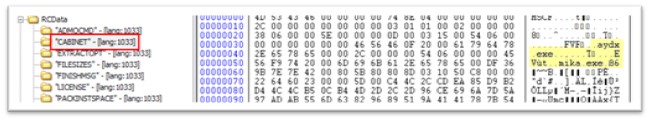

Figure 2: Resources in the file

A CAB (Cabinet) file is a compressed archive file format that is often used to compress and package multiple files into a single file for distribution or installation. A CAB file in the resource section of a PE file can be used for various purposes such as storing additional program files or data, including language-specific resources, or compressing and storing commonly used resources to reduce the size of the executable.

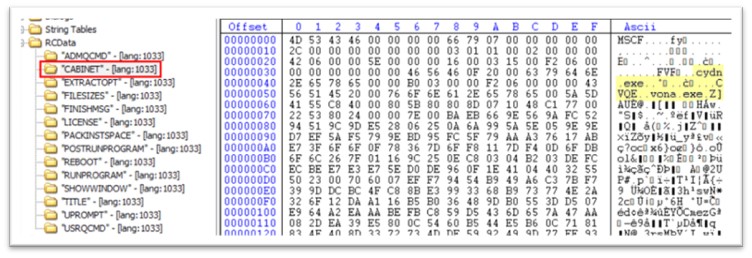

The CABINET holds two executables, cydn.exe and vona.exe.

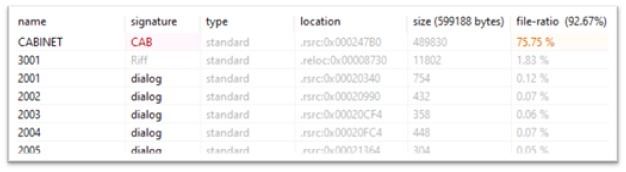

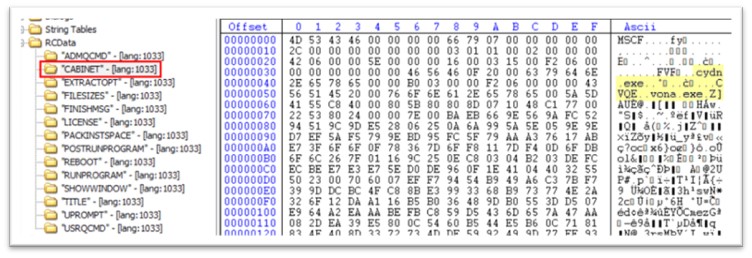

Figure 3: CABINET in resource section

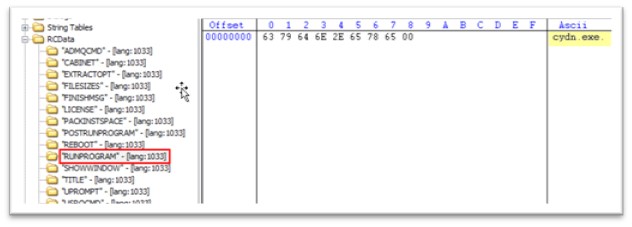

Likewise, under RCDATA, there is another attribute called “RUNPROGRAM”, which starts cydn.exe. RUNPROGRAM in the resource section of a malware file typically refers to a resource that contains instructions for the malware to execute a specific program or command. When the malware is executed, it will load the resource containing the “RUNPROGRAM” command and attempt to execute the specified program or command. This technique is often used by malware authors to execute additional malicious programs or commands on the infected system. For example, the “RUNPROGRAM” resource may contains instructions to download and execute additional malware, or to launch a malicious script or command that can perform various malicious activities such as stealing sensitive data, creating backdoors, or disabling security software.

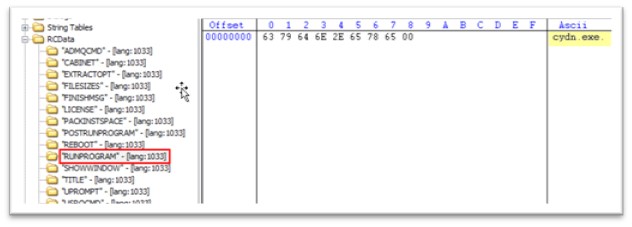

Figure 4: RUNPROGRAM attribute stating “cydn.exe”

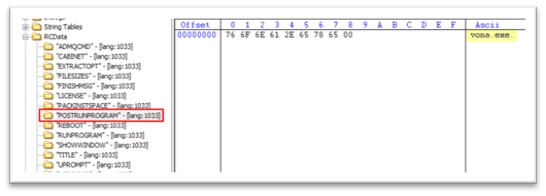

Like RUNPROGRAM, POSTRUNPROGRAM also holds the instruction to run the executable after RUNPROGRAM is executed. Hence, once cydn.exe is executed, vona.exe will be executed.

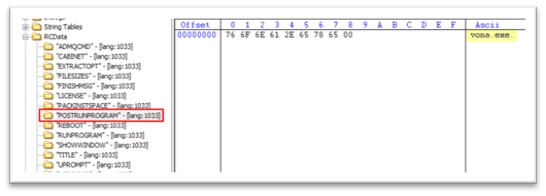

Figure 5: POSTRUNPROGRAM stating “vona.exe”

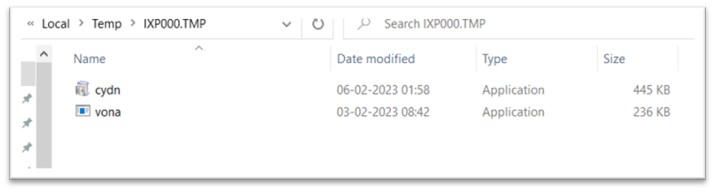

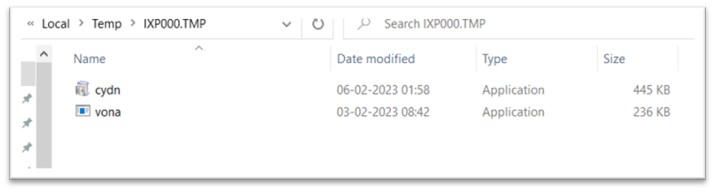

Once WEXTRACT.exe is executed, both cydn.exe and vona.exe is dropped in the TEMP folder. The TEMP folder is a commonly used location for malware to store temporary files and other data, as it is typically writable by any user account and is not usually subject to strict security restrictions. This can make it easier for the malware to operate without raising suspicion or triggering security alerts.

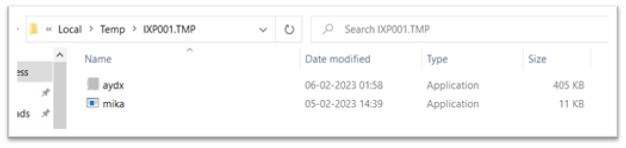

Figure 6: Files dropped in TEMP folder

Stage 2: Analysis of cydn.exe

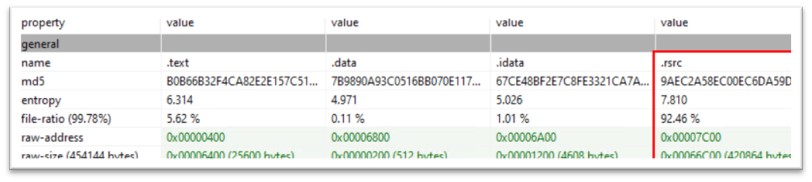

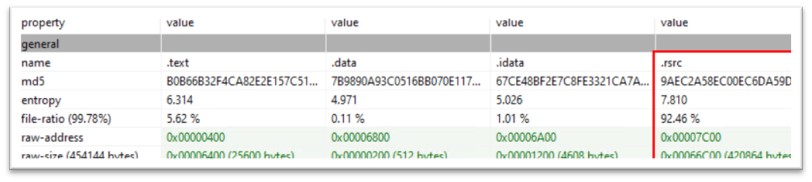

The file showed high file ratio of the resource section, with the entropy of 7.810. Entropy is a measure of the randomness or unpredictability of the data in the file. It is often used as an indicator of whether a file is likely to be malicious or not.

In the case of a PE file, high entropy can indicate that the file contains a significant amount of compressed or encrypted data, or that it has been obfuscated or packed in a way that makes it more difficult to analyze. This can be a common technique used by malware authors to evade detection by antivirus software.

Figure 7: File ratio and entropy of the resource section

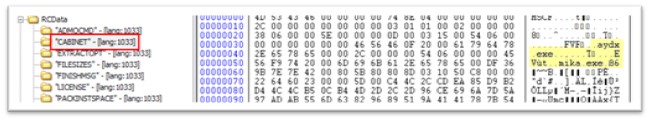

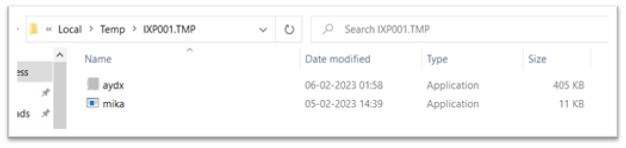

Like the previous file, cydn.exe also had two executables archived in its resource section, named aydx.exe and mika.exe. The “RUNPROGRAM” attribute commands to run aydx.exe and the “POSTRUNPROGRAM” attribute commands to execute mika.exe once aydx.exe is executed. These files are also dropped in TEMP folder.

Figure 8: aydx.exe and mika.exe packed in resource section

Figure 9: Executables dropped in another TEMP folder

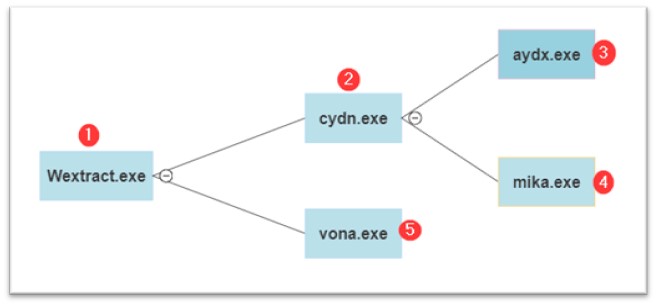

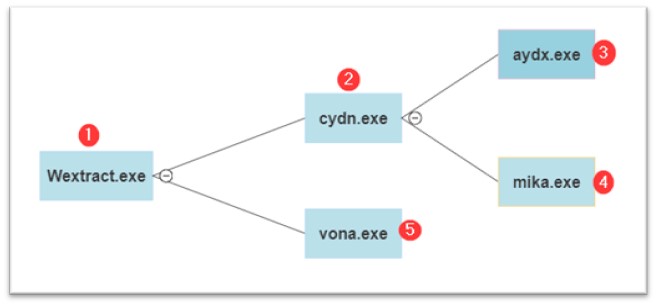

The order of file execution is as follows: First, Wextract.exe and cydn.exe, which have already been discussed, are followed by aydx.exe, and then by mika.exe and vona.exe.

Figure 10: Execution flow

Stage 3: Analysis of aydx.exe

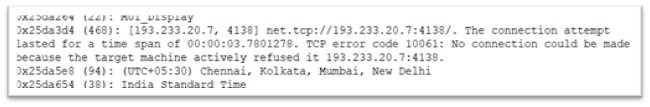

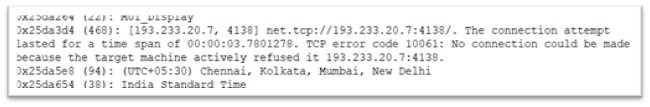

Aydx.exe is a 32-bit Portable Executable file, which is 405Kb and is compiled in C/C++. Once executed, it attempts to make a request to IP address: 193.233.20.7.

Figure 11: Malware trying to connect to IPv4

This IP address is linked with Redline Stealer connecting on port number 4138.

Analysis of mika.exe

Mika.exe is 32-bit Portable Executable, complied in .NET and is just 11 KB in size. The original name of the file is “Healer.exe”. This exe file makes no internet activity but does something in the target machine which assists malwares from further stages to carry out their execution.

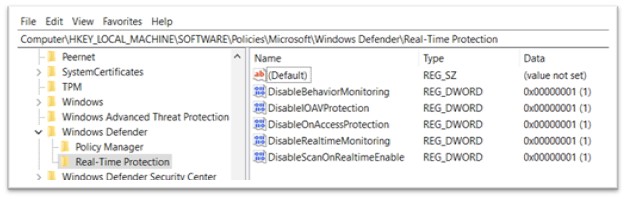

The intent of mika.exe is to turn off Windows Defender in all possible ways. Once mika.exe was executed, this is how the Defender settings of the system looked like:

Figure 12: Real-time protection turned off

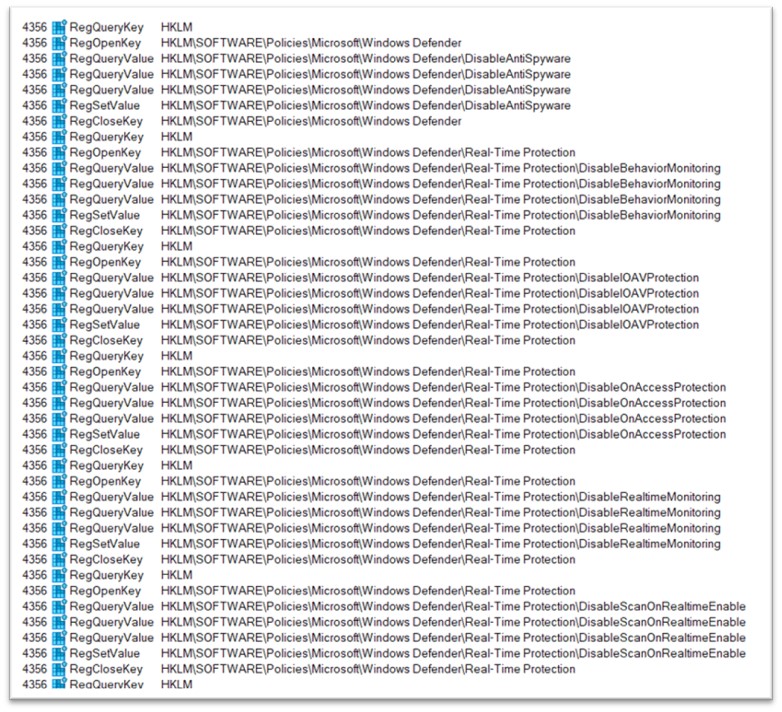

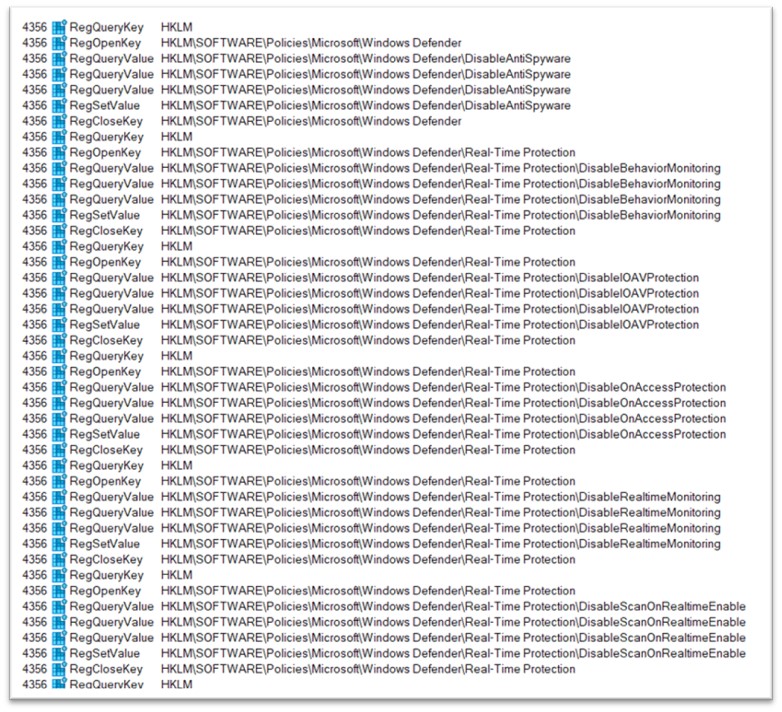

This setting was irreversible and couldn’t be turned back to on via settings of Windows. Following this, logs from Procmon were analyzed and there were entries regarding Windows defender, such as:

Figure 13: Procmon logs

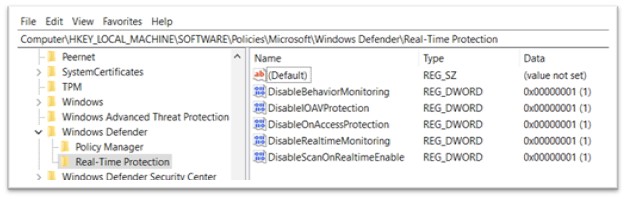

To validate this, Registry was analysed and all the changes were found there. The changes in Registry were found to be in exact order as of Procmon logs. In Windows, the registry is a hierarchical database that stores configuration settings and options for the operating system, as well as for applications and devices. It is used to store information about the hardware, software, user preferences, and system settings on a Windows computer. Following keys are added under Real-Time Protection:

- DisableBehaviourMonitoring

- DisableIOAVProtection

- DisableOnAccessProtection

- DisableRealtimeMonitoring

- DisableScanOnRealitimeEnable

Figure 14: Keys added in Registry

By doing so malware is restricting all the normal users from turning the Windows Defender on. When attackers disable Windows Defender through the registry, the change is likely to persist even if the user or administrator tries to re-enable it through the Windows Defender settings. This allows the attacker to maintain control over the system for a longer period. This supports malwares of further stages to easily execute themselves without any hinderances. This can be leveraged by all the malwares, regardless of their correspondence to this very campaign.

Stage 4: Analysis of vona.exe

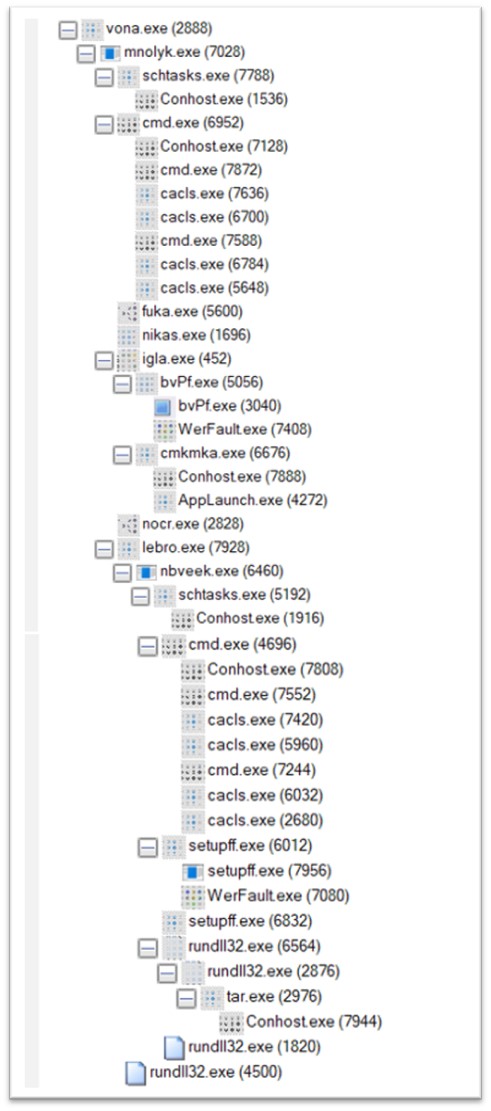

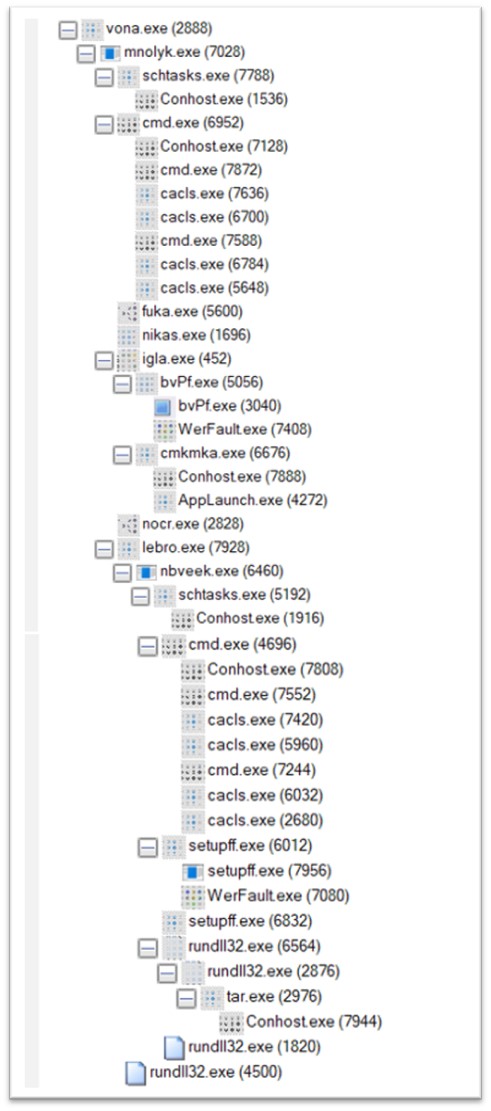

Vona.exe, a variant of the Amadey malware family, is compiled in C/C++ and is 236 KB in size. This is the last file to be executed from the current cluster. When executed, a highly extensive process tree quickly appeared.

Figure 15: Process tree of vona.exe

Stage 5: Analysis of mnolyk.exe

An immediate child process of vona.exe is mnolyk.exe, another Amadey component, is dropped in a folder in TEMP folder.

Figure 16: mnolyk.exe dropped in TEMP folder

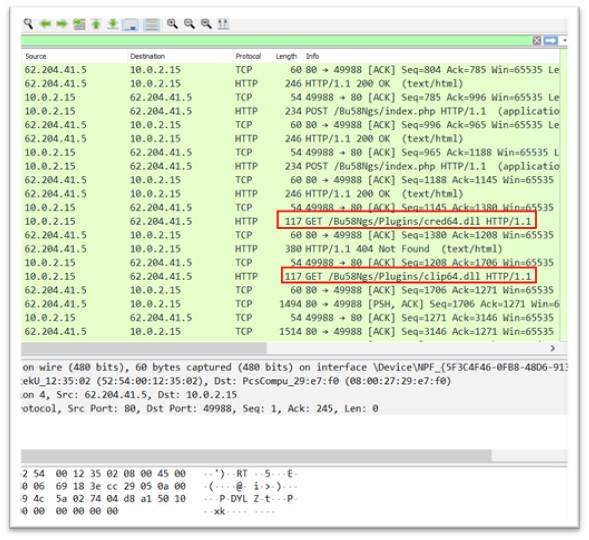

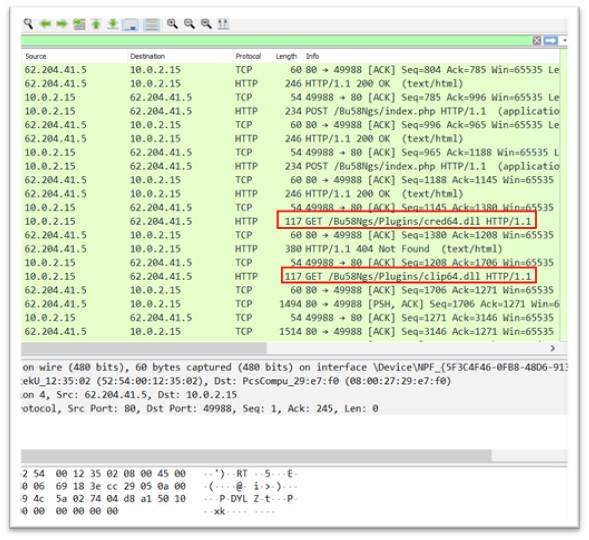

Mnolyk.exe makes active connections to IP addresses 62.204.41.5 and 62.204.41.251

Malicious DLLs are downloaded from 62.204.41.5, which are executed later in the campaign. The target was made to search for two different DLLs, namely cred.dll and clip.dll.

Figure 17: Malicious dlls downloaded

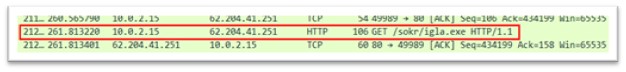

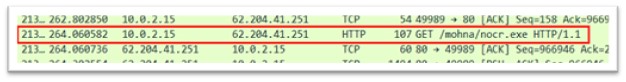

From 62.204.41.251, various exe files are downloaded to the TEMP folder, and later executed. Exes downloaded are:

fuka.exe

Figure 18: fuka.exe

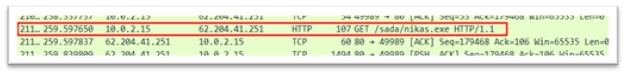

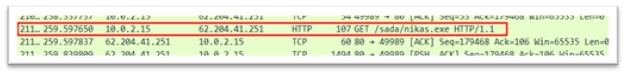

nikas.exe

Figure 19: nikas.exe

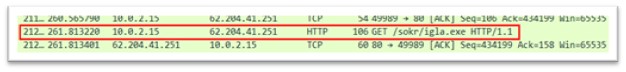

igla.exe

Figure 20: igla.exe

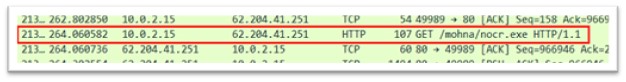

nocr.exe

Figure 21: nocr.exe

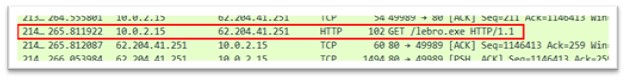

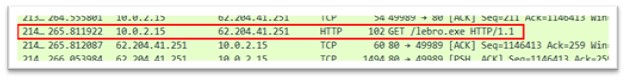

lebro.exe

Figure 22: lebro.exe

Following the execution of mnolyk.exe, a series of schtasks.exe and cacls.exe were executed.

The command line for schtasks.exe is “C:WindowsSystem32schtasks.exe” /Create /SC MINUTE /MO 1 /TN mnolyk.exe /TR “C:UserstestAppDataLocalTemp5eb6b96734mnolyk.exe” /F

- “/Create” – This is the command to create a new scheduled task.

- “/SC MINUTE” – This parameter sets the scheduling interval for the task to “MINUTE”. The task will run every minute.

- “/MO 1” – This parameter sets the repeat count to “1”. The task will run only once.

- “/TN” – This parameter specifies the name of the task. The name should be specified after the “/TN” parameter.

So, the entire command line “schtasks.exe /Create /SC MINUTE /MO 1 /TN” would create a scheduled task that runs once every minute. The name of the task specified is the path to mnolyk.exe.

There were several instances of cacls.exe created. One of them is explained here along with its parameter. The command line is “CACLS ”mnolyk.exe” /P “test:R” /E”

- “CACLS” – This is the command to change the ACL of a file.

- “mnolyk.exe” – This is the file for which the ACL will be modified.

- “/P test:R” – This parameter specifies the permission change for a user named “test”. The “:R” at the end indicates that the “test” user will be granted “Read” permission.

- “/E” – This parameter specifies that the ACL change will be made to the file’s effective ACL. The effective ACL is the actual set of permissions that are applied to the file.

So, the entire command line “CACLS mnolyk.exe /P test:R /E” would grant the “test” user or group “Read” permission to the “mnolyk.exe” file. Hence the user “test” can neither write nor delete this file. If in place of “/P test:R”, “/P test:N” was mentioned, which is mentioned in one of the command line, it would give “None” permission to the user.

Stage 6: Analyzing fuka.exe, nikas.exe, igla.exe, nocr.exe and lebro.exe

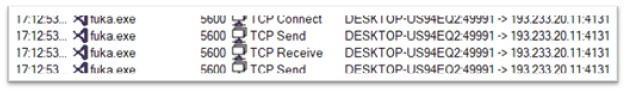

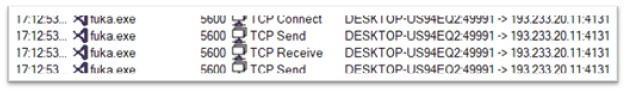

Fuka.exe

Fukka.exe, a variant of the Redline Stealer malware family, is 175 KB and is compiled in .NET. The original name of the file is Samarium.exe. It shows some network activity with IP 193.233.20.11.

Figure 23: Network activity of fuka.exe

Nikas.exe

Nikas.exe is 248 KB executable file compiled in C/C++. It disables automatic updates for Windows and checks the status of all the sub-fields of Real-Time Protection that were previously changed by mika.exe. No network activity was found during replication.

Igla.exe

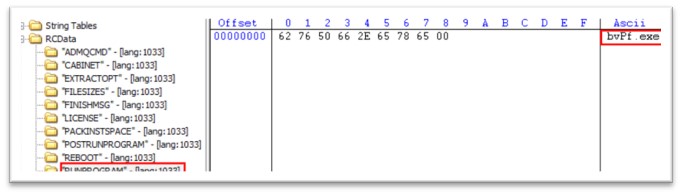

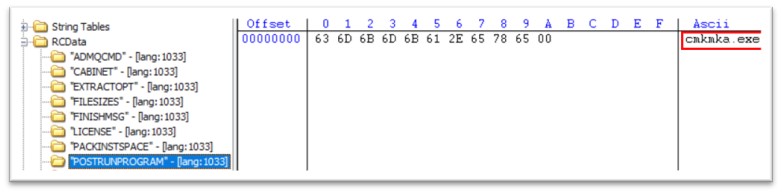

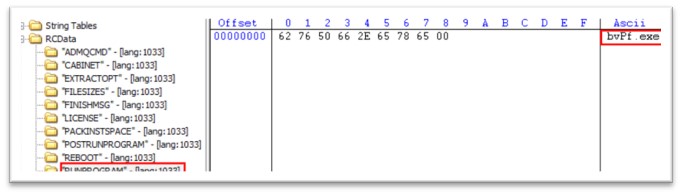

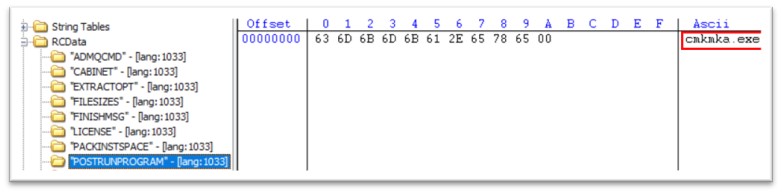

Igla.exe is 520 KB file, compiled in C/C++. The original name of the file is WEXTRACT.EXE.MUI. Like we saw in cydn.exe, this PE has also two more exes packed in its resource section, bvPf.exe and cmkmka.exe. Once igla.exe is executed, bvPf.exe is executed, followed by cmkmka.exe.

Figure 24: RUNPROGRAM attribute in igla.exe

Figure 25: POSTRUNPROGRAM attribute in igla.exe

bvPf.exe

bvPf.exe is 306 KB in size and is compiled in C/C++. The original filename is nightskywalker.exe. The file is dropped in a folder in TEMP folder of the system.

The exe has tried connecting to 193.233.20.11, but server did not respond, and no communication took place.

cmkmka.exe

cmkmka.exe is 32-bit PE file, 283.5 KB in size. It further launches AppLaunch.exe which communicates to C2.

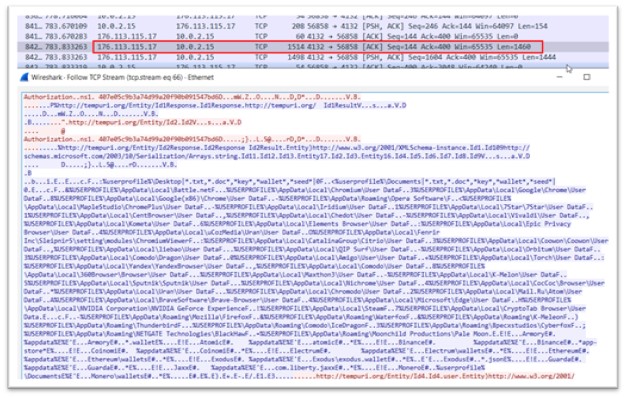

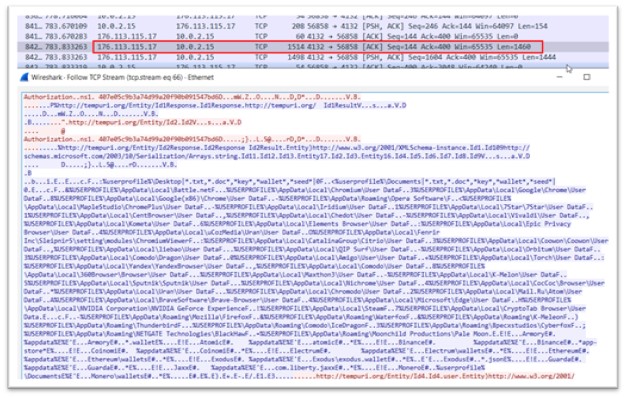

It communicates to the IP address: 176.113.115.17 which is an active C2 for Redline Stealer and connects to the port 4132.

Figure 26: Data exfiltration

The blue-colored content in the data indicates the information being transmitted from the Command and Control (C2) server, which is providing instructions to the malware regarding the specific data that needs to be retrieved along with their corresponding paths. These paths include user profiles of different web browsers, various crypto wallet paths, and other related data.

As a response, all the data residing at the specified paths is sent back to the C2 server of the malware. This includes all the profiles of different web browsers, information related to crypto wallets, and even user-related data from the Windows operating system. This process allows the C2 server to collect a vast amount of sensitive information from the infected system, which could be exploited by the attackers for malicious purposes.

Nocr.exe

Nocr.exe, a component of Redline Stealer, is a 175 KB .NET binary. The original name of the file is Alary.exe. It communicates to the IP address 176.113.115.17.

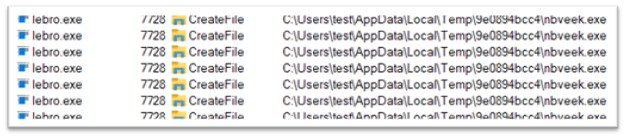

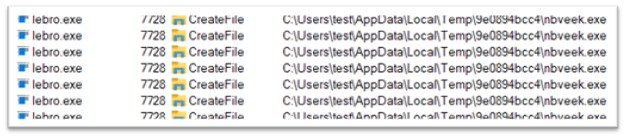

Lebro.exe

Lebro.exe, a component of Amadey, is a 235 KB file, compiled in C/C++. Lebro.exe is responsible for executing nbveek.exe, which is a next stage of the malware. The file is again dropped in TEMP folder.

Figure 27: Dropping another executable in TEMP folder

Stage 7: Analyzing nbveek.exe

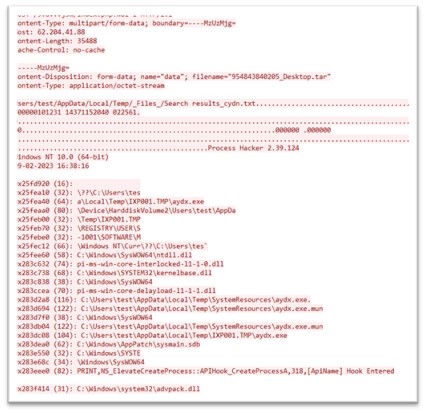

The hashes of lebro.exe and nbveek.exe are same, they are the same binaries, hence it is Amadey. It is connecting to IP 62.204.41.88.

Figure 28: Network activity of nbveek.exe

The target system executes a php file, and the content of file includes the command to download another exe called setupff.exe. This exe is downloaded to the TEMP folder.

Before setupff.exe is executed, again the series of schtasks.exe and cacls.exe are executed which were seen previously also. The same parameters were passed for nbveek.exe as they were for mnolyk.exe.

Setupff.exe

Setupff.exe is compiled in C/C++ and is 795 KB. The file could not execute and threw Windows error.

Stage 8: Final stage

Later, another instance of setupff.exe was created which further invokes multiple instances of rundll32.exe. Here, the two dlls downloaded by mnolyk.exe, clip64.dll and cred64.dll, are executed through rundll32.exe. McAfee Labs detects these dlls to be Amadey maware.

The network activity shows the dll to be connecting to 62.204.41.88. This dll again starts exfiltrating data to C2:

Figure 29:Data exfiltration

To conclude, the threat posed by the multi-stage attack that drops the Amadey botnet, and subsequently Redline Stealer, is significant and requires constant vigilance from both consumers and security professionals. By using the Amadey botnet as a delivery mechanism for other malware, attackers can leverage these same capabilities to evade detection and maintain persistence on infected computers. They can use Amadey to drop a wide range of malware, such as spyware, ransomware, and trojans, which can be used for a variety of malicious purposes, such as stealing sensitive information, encrypting files for ransom, or taking control of a computer for use in a larger botnet. Our analysis of various samples of this attack has revealed that the Amadey botnet distributes malware from multiple families and is not restricted to Redline Stealer alone.

At McAfee, we are committed to providing our customers with robust and effective antivirus and anti-malware solutions that can detect and protect against threats like the Amadey botnet and other malware families. Our security software uses a combination of signature, machine learning, threat intelligence and behavioral-based detection techniques to identify and stop threats before they can cause damage.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs):

| File Type |

SHA-256 |

Product |

Detection |

| .exe |

80fed7cd4c7d7cb0c05fe128ced6ab2b9b3d7f03edcf5ef532c8236f00ee7376 |

Total Protection and LiveSafe |

Downloader-FCND

Lockbit-FSWW

PWS-FDON |

| .exe |

d8e9b2d3afd0eab91f94e1a1a1a0a97aa2974225f4f086a66e76dbf4b705a800 |

Total Protection and LiveSafe |

PWS-FDON

Lockbit-FSWW |

| .exe |

1d51e0964268b35afb43320513ad9837ec6b1c0bd0e56065ead5d99b385967b5 |

Total Protection and LiveSafe |

Lockbit-FSWW |

| .exe |

850cd190aaeebcf1505674d97f51756f325e650320eaf76785d954223a9bee38 |

Total Protection and LiveSafe |

PWS-FDON |

| .exe |

6cbcf0bb90ae767a8c554cdfa90723e6b1127e98cfa19a2259dd57813d27e116 |

Total Protection and LiveSafe |

Downloader-FCND |

| .exe |

6cbcf0bb90ae767a8c554cdfa90723e6b1127e98cfa19a2259dd57813d27e116 |

Total Protection and LiveSafe |

Downloader-FCND |

| .exe |

8020580744f6861a611e99ba17e92751499e4b0f013d66a103fb38c5f256bbb2 |

Total Protection and LiveSafe |

AgentTesla-FCYU |

| .exe |

021ae2fadbc8bc4e83013de03902e6e97c2815ab821adaa58037e562a6b2357b |

Total Protection and LiveSafe |

Lockbit-FSWW |

| .exe |

aab1460440bee10e2efec9b5c83ea20ed85e7a17d4ed3b4a19341148255d54b1 |

Total Protection and LiveSafe |

Lockbit-FSWW |

| .exe |

54ce28a037eea87448e65bc25f8d3a38ddd4b4679516cc59899b77150aa46fcc |

Total Protection and LiveSafe |

GenericRXVK-HF |

| .exe |

0cca99711baf600eb030bbfcf279faf74c564084e733df3d9e98bea3e4e2f45f |

Total Protection and LiveSafe |

AgentTesla-FCYU |

| .exe |

ad1d5475d737c09e3c48f7996cd407c992c1bb5601bcc6c6287eb80cde3d852b |

Total Protection and LiveSafe |

Downloader-FCND |

| .exe |

ad1d5475d737c09e3c48f7996cd407c992c1bb5601bcc6c6287eb80cde3d852b |

Total Protection and LiveSafe |

Downloader-FCND |

| .exe |

d40d2bfa9fcbf980f76ce224ab6037ebd2b081cb518fa65b8e208f84bc155e41 |

Total Protection and LiveSafe |

GenericRXVJ-QP |

| .dll |

cdd4072239d8a62bf134e9884ef2829d831efaf3f6f7f71b7266af29df145dd0 |

Total Protection and LiveSafe |

PWS-FDOE |

| .dll |

10ee53988bcfbb4bb9c8928ea96c4268bd64b9dfd1f28c6233185e695434d2f8 |

Total Protection and LiveSafe |

Trojan-FUUW |

| .dll |

3492ed949b0d1cbd720eae940d122d6a791df098506c24517da0cc149089f405 |

Total Protection and LiveSafe |

Trojan-FUUW |

| IPv4 |

193.233.20.7 |

|

|

| IPv4 |

62.204.41.5 |

|

|

| IPv4 |

62.204.41.251 |

|

|

| IPv4 |

193.233.20.11 |

|

|

| IPv4 |

176.113.115.17 |

|

|

| IPv4 |

62.204.41.88 |

|

|

The post Deconstructing Amadey’s Latest Multi-Stage Attack and Malware Distribution appeared first on McAfee Blog.