Aisuru, the botnet responsible for a series of record-smashing distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks this year, recently was overhauled to support a more low-key, lucrative and sustainable business: Renting hundreds of thousands of infected Internet of Things (IoT) devices to proxy services that help cybercriminals anonymize their traffic. Experts says a glut of proxies from Aisuru and other sources is fueling large-scale data harvesting efforts tied to various artificial intelligence (AI) projects, helping content scrapers evade detection by routing their traffic through residential connections that appear to be regular Internet users.

First identified in August 2024, Aisuru has spread to at least 700,000 IoT systems, such as poorly secured Internet routers and security cameras. Aisuru’s overlords have used their massive botnet to clobber targets with headline-grabbing DDoS attacks, flooding targeted hosts with blasts of junk requests from all infected systems simultaneously.

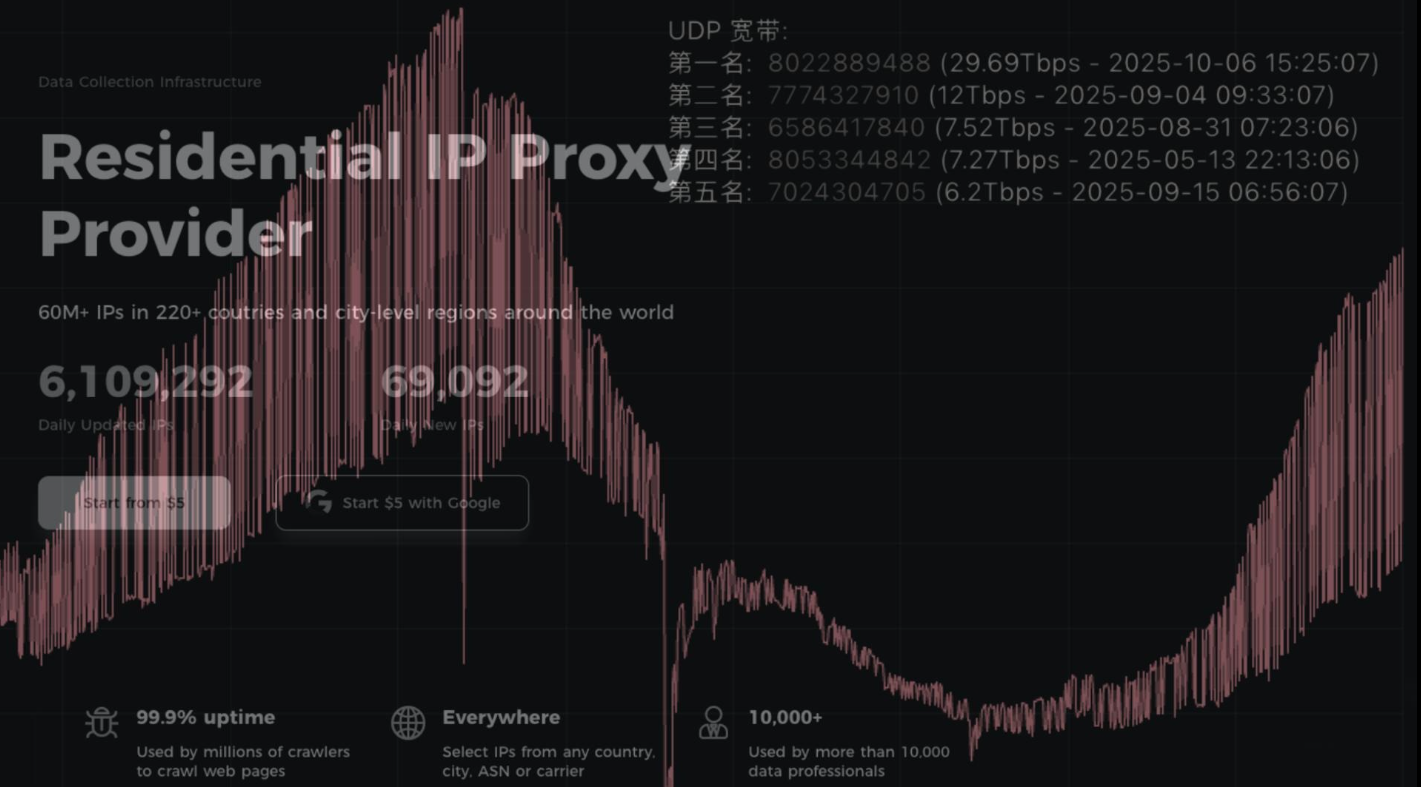

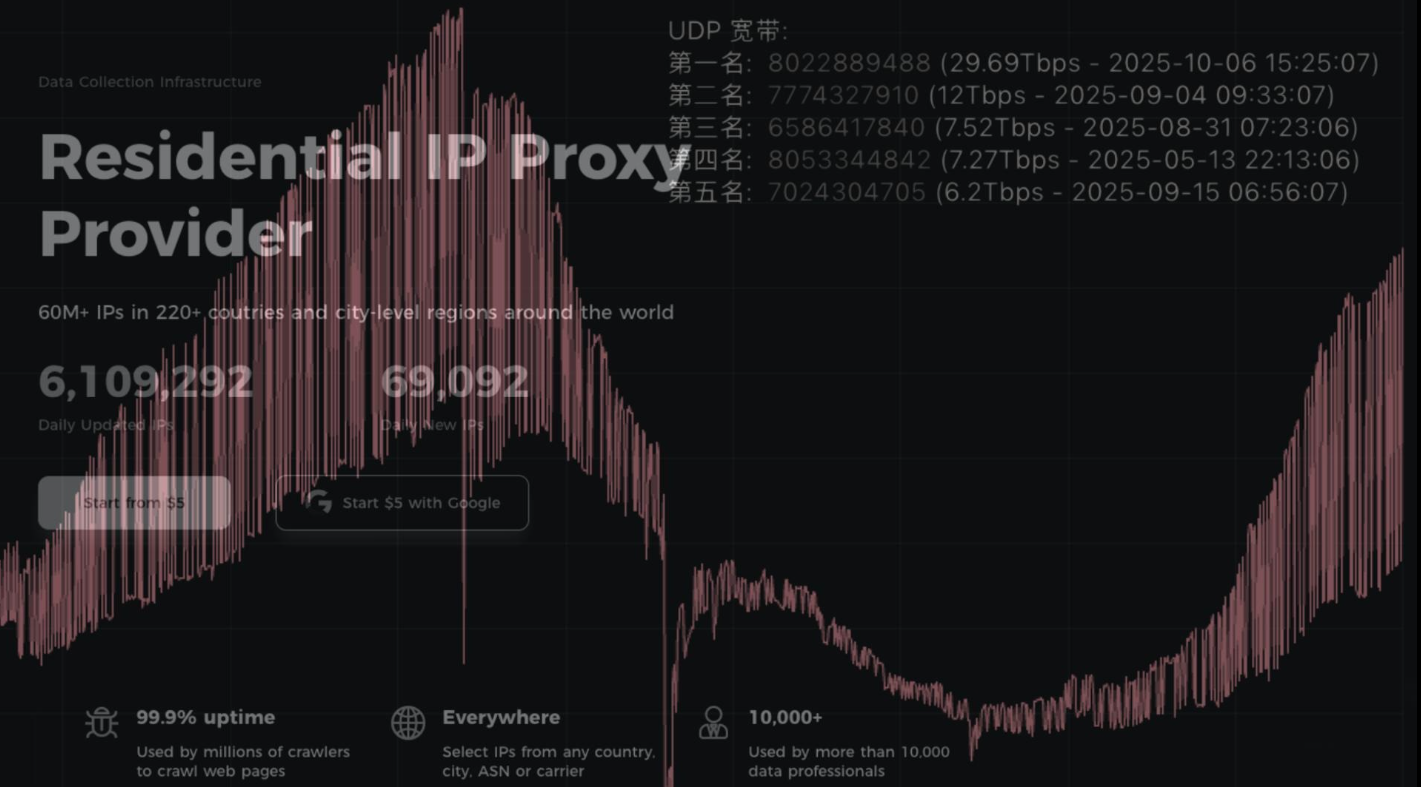

In June, Aisuru hit KrebsOnSecurity.com with a DDoS clocking at 6.3 terabits per second — the biggest attack that Google had ever mitigated at the time. In the weeks and months that followed, Aisuru’s operators demonstrated DDoS capabilities of nearly 30 terabits of data per second — well beyond the attack mitigation capabilities of most Internet destinations.

These digital sieges have been particularly disruptive this year for U.S.-based Internet service providers (ISPs), in part because Aisuru recently succeeded in taking over a large number of IoT devices in the United States. And when Aisuru launches attacks, the volume of outgoing traffic from infected systems on these ISPs is often so high that it can disrupt or degrade Internet service for adjacent (non-botted) customers of the ISPs.

“Multiple broadband access network operators have experienced significant operational impact due to outbound DDoS attacks in excess of 1.5Tb/sec launched from Aisuru botnet nodes residing on end-customer premises,” wrote Roland Dobbins, principal engineer at Netscout, in a recent executive summary on Aisuru. “Outbound/crossbound attack traffic exceeding 1Tb/sec from compromised customer premise equipment (CPE) devices has caused significant disruption to wireline and wireless broadband access networks. High-throughput attacks have caused chassis-based router line card failures.”

The incessant attacks from Aisuru have caught the attention of federal authorities in the United States and Europe (many of Aisuru’s victims are customers of ISPs and hosting providers based in Europe). Quite recently, some of the world’s largest ISPs have started informally sharing block lists identifying the rapidly shifting locations of the servers that the attackers use to control the activities of the botnet.

Experts say the Aisuru botmasters recently updated their malware so that compromised devices can more easily be rented to so-called “residential proxy” providers. These proxy services allow paying customers to route their Internet communications through someone else’s device, providing anonymity and the ability to appear as a regular Internet user in almost any major city worldwide.

From a website’s perspective, the IP traffic of a residential proxy network user appears to originate from the rented residential IP address, not from the proxy service customer. Proxy services can be used in a legitimate manner for several business purposes — such as price comparisons or sales intelligence. But they are massively abused for hiding cybercrime activity (think advertising fraud, credential stuffing) because they can make it difficult to trace malicious traffic to its original source.

And as we’ll see in a moment, this entire shadowy industry appears to be shifting its focus toward enabling aggressive content scraping activity that continuously feeds raw data into large language models (LLMs) built to support various AI projects.

‘INSANE’ GROWTH

Riley Kilmer is co-founder of spur.us, a service that tracks proxy networks. Kilmer said all of the top proxy services have grown exponentially over the past six months — with some adding between 10 to 200 times more proxies for rent.

“I just checked, and in the last 90 days we’ve seen 250 million unique residential proxy IPs,” Kilmer said. “That is insane. That is so high of a number, it’s unheard of. These proxies are absolutely everywhere now.”

To put Kilmer’s comments in perspective, here was Spur’s view of the Top 10 proxy networks by approximate install base, circa May 2025:

AUPROXIES_PROXY 66,097

RAYOBYTE_PROXY 43,894

OXYLABS_PROXY 43,008

WEBSHARE_PROXY 39,800

IPROYAL_PROXY 32,723

PROXYCHEAP_PROXY 26,368

IPIDEA_PROXY 26,202

MYPRIVATEPROXY_PROXY 25,287

HYPE_PROXY 18,185

MASSIVE_PROXY 17,152

Today, Spur says it is tracking an unprecedented spike in available proxies across all providers, including;

LUMINATI_PROXY 11,856,421

NETNUT_PROXY 10,982,458

ABCPROXY_PROXY 9,294,419

OXYLABS_PROXY 6,754,790

IPIDEA_PROXY 3,209,313

EARNFM_PROXY 2,659,913

NODEMAVEN_PROXY 2,627,851

INFATICA_PROXY 2,335,194

IPROYAL_PROXY 2,032,027

YILU_PROXY 1,549,155

Reached for comment about the apparent rapid growth in their proxy network, Oxylabs (#4 on Spur’s list) said while their proxy pool did grow recently, it did so at nowhere near the rate cited by Spur.

“We don’t systematically track other providers’ figures, and we’re not aware of any instances of 10× or 100× growth, especially when it comes to a few bigger companies that are legitimate businesses,” the company said in a written statement.

Bright Data was formerly known as Luminati Networks, the name that is currently at the top of Spur’s list of the biggest residential proxy networks, with more than 11 million proxies. Bright Data likewise told KrebsOnSecurity that Spur’s current estimates of its proxy network are dramatically overstated and inaccurate.

“We did not actively initiate nor do we see any 10x or 100x expansion of our network, which leads me to believe that someone might be presenting these IPs as Bright Data’s in some way,” said Rony Shalit, Bright Data’s chief compliance and ethics officer. “In many cases in the past, due to us being the leading data collection proxy provider, IPs were falsely tagged as being part of our network, or while being used by other proxy providers for malicious activity.”

“Our network is only sourced from verified IP providers and a robust opt-in only residential peers, which we work hard and in complete transparency to obtain,” Shalit continued. “Every DC, ISP or SDK partner is reviewed and approved, and every residential peer must actively opt in to be part of our network.”

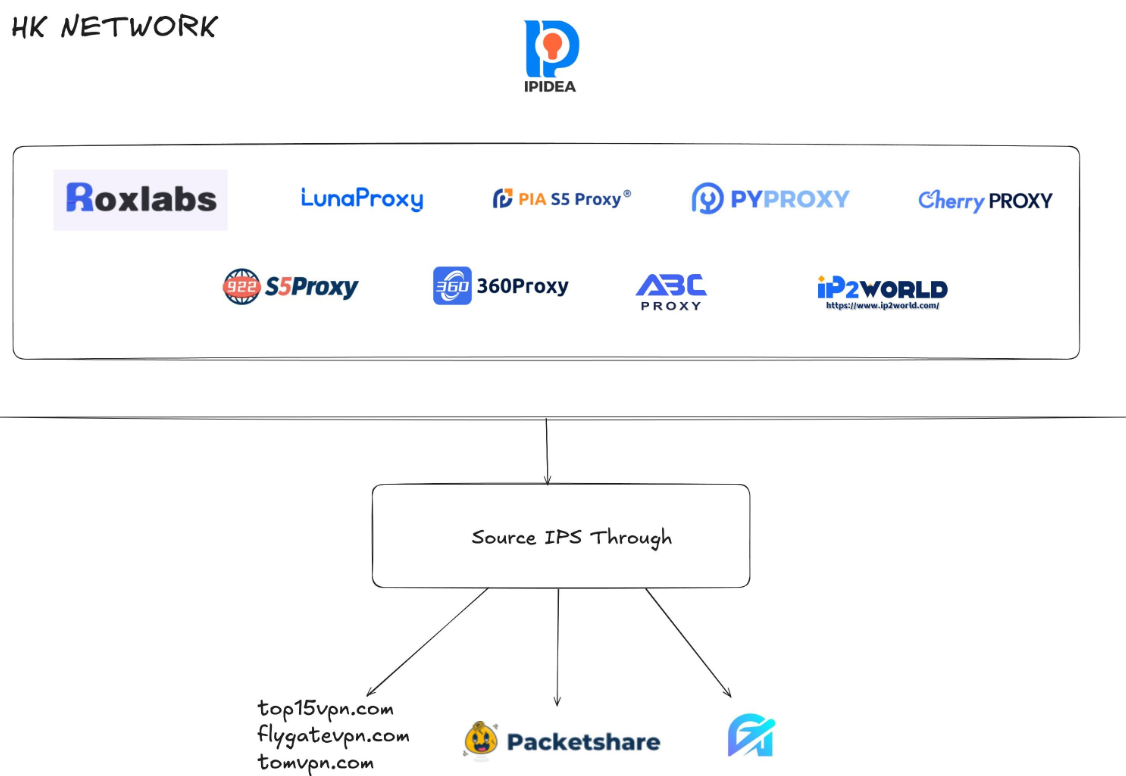

HK NETWORK

Even Spur acknowledges that Luminati and Oxylabs are unlike most other proxy services on their top proxy providers list, in that these providers actually adhere to “know-your-customer” policies, such as requiring video calls with all customers, and strictly blocking customers from reselling access.

Benjamin Brundage is founder of Synthient, a startup that helps companies detect proxy networks. Brundage said if there is increasing confusion around which proxy networks are the most worrisome, it’s because nearly all of these lesser-known proxy services have evolved into highly incestuous bandwidth resellers. What’s more, he said, some proxy providers do not appreciate being tracked and have been known to take aggressive steps to confuse systems that scan the Internet for residential proxy nodes.

Brundage said most proxy services today have created their own software development kit or SDK that other app developers can bundle with their code to earn revenue. These SDKs quietly modify the user’s device so that some portion of their bandwidth can be used to forward traffic from proxy service customers.

“Proxy providers have pools of constantly churning IP addresses,” he said. “These IP addresses are sourced through various means, such as bandwidth-sharing apps, botnets, Android SDKs, and more. These providers will often either directly approach resellers or offer a reseller program that allows users to resell bandwidth through their platform.”

Many SDK providers say they require full consent before allowing their software to be installed on end-user devices. Still, those opt-in agreements and consent checkboxes may be little more than a formality for cybercriminals like the Aisuru botmasters, who can earn a commission each time one of their infected devices is forced to install some SDK that enables one or more of these proxy services.

Depending on its structure, a single provider may operate hundreds of different proxy pools at a time — all maintained through other means, Brundage said.

“Often, you’ll see resellers maintaining their own proxy pool in addition to an upstream provider,” he said. “It allows them to market a proxy pool to high-value clients and offer an unlimited bandwidth plan for cheap reduce their own costs.”

Some proxy providers appear to be directly in league with botmasters. Brundage identified one proxy provider that was aggressively advertising cheap and plentiful bandwidth to content scraping companies. After scanning that provider’s pool of available proxies, Brundage said he found a one-to-one match with IP addresses he’d previously mapped to the Aisuru botnet.

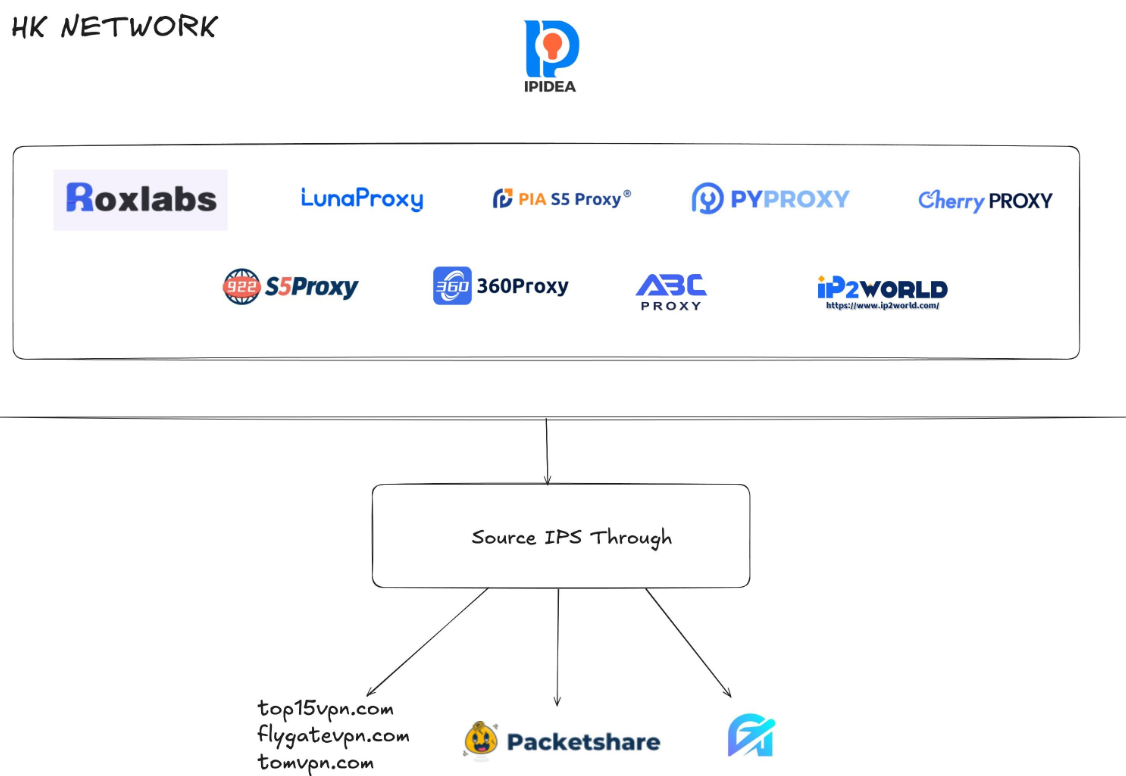

Brundage says that by almost any measurement, the world’s largest residential proxy service is IPidea, a China-based proxy network. IPidea is #5 on Spur’s Top 10, and Brundage said its brands include ABCProxy (#3), Roxlabs, LunaProxy, PIA S5 Proxy, PyProxy, 922Proxy, 360Proxy, IP2World, and Cherry Proxy. Spur’s Kilmer said they also track Yilu Proxy (#10) as IPidea.

Brundage said all of these providers operate under a corporate umbrella known on the cybercrime forums as “HK Network.”

“The way it works is there’s this whole reseller ecosystem, where IPidea will be incredibly aggressive and approach all these proxy providers with the offer, ‘Hey, if you guys buy bandwidth from us, we’ll give you these amazing reseller prices,’” Brundage explained. “But they’re also very aggressive in recruiting resellers for their apps.”

A graphic depicting the relationship between proxy providers that Synthient found are white labeling IPidea proxies. Image: Synthient.com.

Those apps include a range of low-cost and “free” virtual private networking (VPN) services that indeed allow users to enjoy a free VPN, but which also turn the user’s device into a traffic relay that can be rented to cybercriminals, or else parceled out to countless other proxy networks.

“They have all this bandwidth to offload,” Brundage said of IPidea and its sister networks. “And they can do it through their own platforms, or they go get resellers to do it for them by advertising on sketchy hacker forums to reach more people.”

One of IPidea’s core brands is 922S5Proxy, which is a not-so-subtle nod to the 911S5Proxy service that was hugely popular between 2015 and 2022. In July 2022, KrebsOnSecurity published a deep dive into 911S5Proxy’s origins and apparent owners in China. Less than a week later, 911S5Proxy announced it was closing down after the company’s servers were massively hacked.

That 2022 story named Yunhe Wang from Beijing as the apparent owner and/or manager of the 911S5 proxy service. In May 2024, the U.S. Department of Justice arrested Mr Wang, alleging that his network was used to steal billions of dollars from financial institutions, credit card issuers, and federal lending programs. At the same time, the U.S. Treasury Department announced sanctions against Wang and two other Chinese nationals for operating 911S5Proxy.

The website for 922Proxy.

DATA SCRAPING FOR AI

In recent months, multiple experts who track botnet and proxy activity have shared that a great deal of content scraping which ultimate benefits AI companies is now leveraging these proxy networks to further obfuscate their aggressive data-slurping activity. That’s because by routing it through residential IP addresses, content scraping firms can make their traffic far trickier to filter out.

“It’s really difficult to block, because there’s a risk of blocking real people,” Spur’s Kilmer said of the LLM scraping activity that is fed through individual residential IP addresses, which are often shared by multiple customers at once.

Kilmer says the AI industry has brought a veneer of legitimacy to residential proxy business, which has heretofore mostly been associated with sketchy affiliate money making programs, automated abuse, and unwanted Internet traffic.

“Web crawling and scraping has always been a thing, but AI made it like a commodity, data that had to be collected,” Kilmer said. “Everybody wanted to monetize their own data pots, and how they monetize that is different across the board.”

Kilmer said many LLM-related scrapers rely on residential proxies in cases where the content provider has restricted access to their platform in some way, such as forcing interaction through an app, or keeping all content behind a login page with multi-factor authentication.

“Where the cost of data is out of reach — there is some exclusivity or reason they can’t access the data — they’ll turn to residential proxies so they look like a real person accessing that data,” Kilmer said of the content scraping efforts.

Aggressive AI crawlers increasingly are overloading community-maintained infrastructure, causing what amounts to persistent DDoS attacks on vital public resources. A report earlier this year from LibreNews found some open-source projects now see as much as 97 percent of their traffic originating from AI company bots, dramatically increasing bandwidth costs, service instability, and burdening already stretched-thin maintainers.

Cloudflare is now experimenting with tools that will allow content creators to charge a fee to AI crawlers to scrape their websites. The company’s “pay-per-crawl” feature is currently in a private beta, but it lets publishers set their own prices that bots must pay before scraping content.

On October 22, the social media and news network Reddit sued Oxylabs (PDF) and several other proxy providers, alleging that their systems enabled the mass-scraping of Reddit user content even though Reddit had taken steps to block such activity.

“Recognizing that Reddit denies scrapers like them access to its site, Defendants scrape the data from Google’s search results instead,” the lawsuit alleges. “They do so by masking their identities, hiding their locations, and disguising their web scrapers as regular people (among other techniques) to circumvent or bypass the security restrictions meant to stop them.”

Denas Grybauskas, chief governance and strategy officer at Oxylabs, said the company was shocked and disappointed by the lawsuit.

“Reddit has made no attempt to speak with us directly or communicate any potential concerns,” Grybauskas said in a written statement. “Oxylabs has always been and will continue to be a pioneer and an industry leader in public data collection, and it will not hesitate to defend itself against these allegations. Oxylabs’ position is that no company should claim ownership of public data that does not belong to them. It is possible that it is just an attempt to sell the same public data at an inflated price.”

As big and powerful as Aisuru may be, it is hardly the only botnet that is contributing to the overall broad availability of residential proxies. For example, on June 5 the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center warned that an IoT malware threat dubbed BADBOX 2.0 had compromised millions of smart-TV boxes, digital projectors, vehicle infotainment units, picture frames, and other IoT devices.

In July 2025, Google filed a lawsuit in New York federal court against the Badbox botnet’s alleged perpetrators. Google said the Badbox 2.0 botnet “compromised more than 10 million uncertified devices running Android’s open-source software, which lacks Google’s security protections. Cybercriminals infected these devices with pre-installed malware and exploited them to conduct large-scale ad fraud and other digital crimes.”

A FAMILIAR DOMAIN NAME

Brundage said the Aisuru botmasters have their own SDK, and for some reason part of its code tells many newly-infected systems to query the domain name fuckbriankrebs[.]com. This may be little more than an elaborate “screw you” to this site’s author: One of the botnet’s alleged partners goes by the handle “Forky,” and was identified in June by KrebsOnSecurity as a young man from Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Brundage noted that only systems infected with Aisuru’s Android SDK will be forced to resolve the domain. Initially, there was some discussion about whether the domain might have some utility as a “kill switch” capable of disrupting the botnet’s operations, although Brundage and others interviewed for this story say that is unlikely.

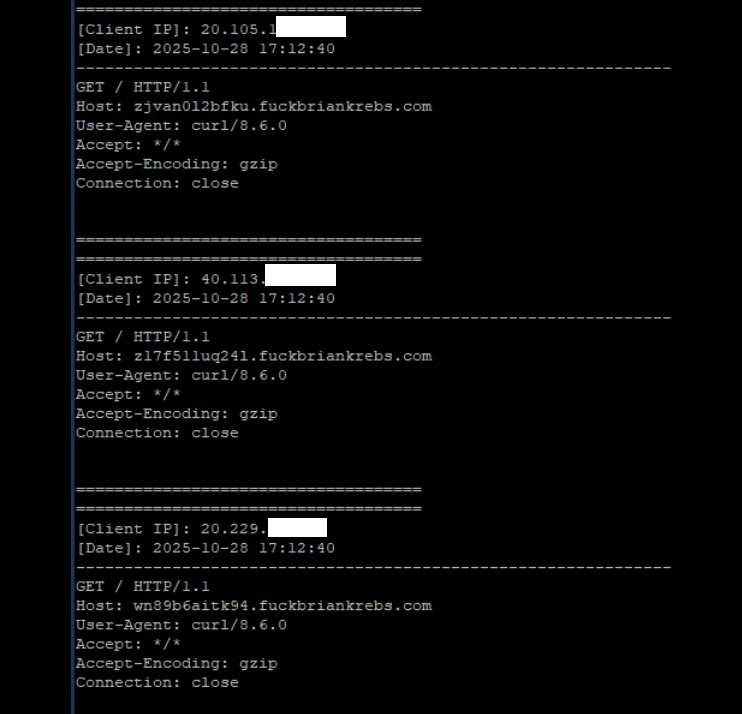

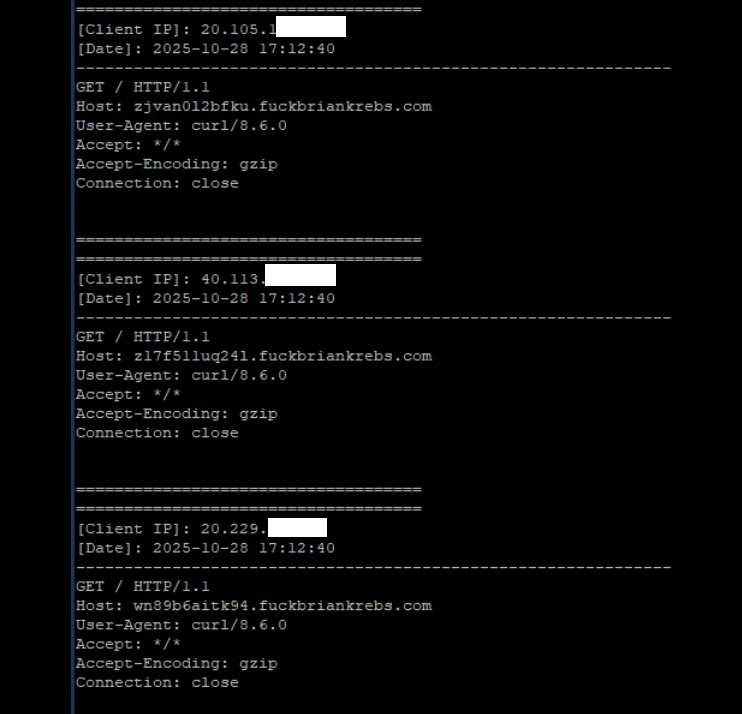

A tiny sample of the traffic after a DNS server was enabled on the newly registered domain fuckbriankrebs dot com. Each unique IP address requested its own unique subdomain. Image: Seralys.

For one thing, they said, if the domain was somehow critical to the operation of the botnet, why was it still unregistered and actively for-sale? Why indeed, we asked. Happily, the domain name was deftly snatched up last week by Philippe Caturegli, “chief hacking officer” for the security intelligence company Seralys.

Caturegli enabled a passive DNS server on that domain and within a few hours received more than 700,000 requests for unique subdomains on fuckbriankrebs[.]com.

But even with that visibility into Aisuru, it is difficult to use this domain check-in feature to measure its true size, Brundage said. After all, he said, the systems that are phoning home to the domain are only a small portion of the overall botnet.

“The bots are hardcoded to just spam lookups on the subdomains,” he said. “So anytime an infection occurs or it runs in the background, it will do one of those DNS queries.”

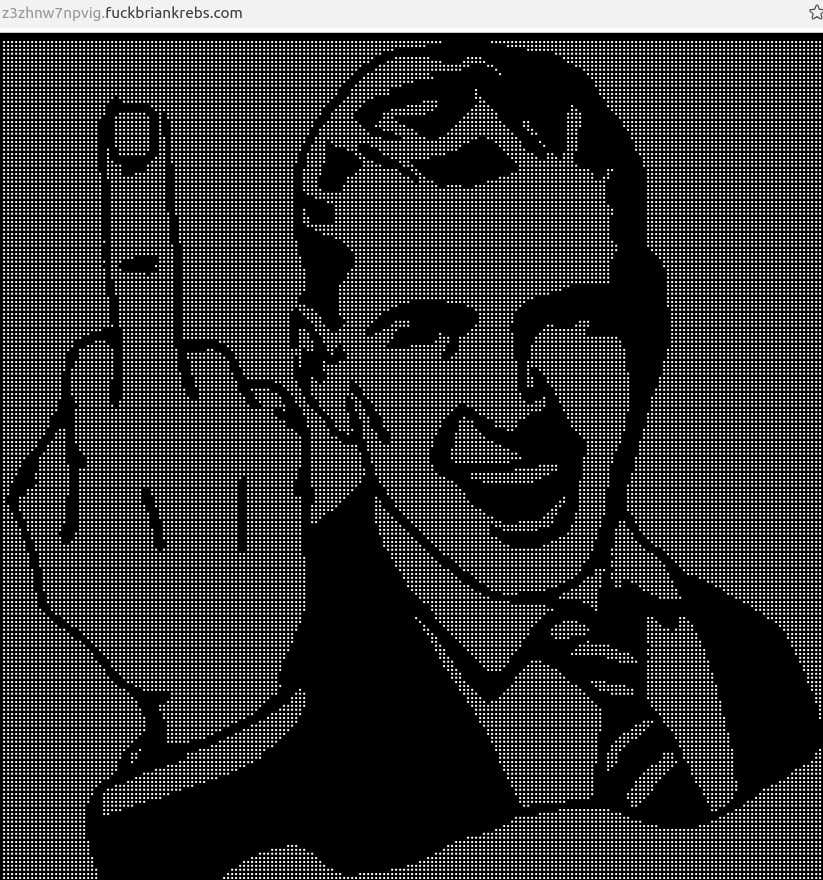

Caturegli briefly configured all subdomains on fuckbriankrebs dot com to display this ASCII art image to visiting systems today.

The domain fuckbriankrebs[.]com has a storied history. On its initial launch in 2009, it was used to spread malicious software by the Cutwail spam botnet. In 2011, the domain was involved in a notable DDoS against this website from a botnet powered by Russkill (a.k.a. “Dirt Jumper”).

Domaintools.com finds that in 2015, fuckbriankrebs[.]com was registered to an email address attributed to David “Abdilo” Crees, a 27-year-old Australian man sentenced in May 2025 to time served for cybercrime convictions related to the Lizard Squad hacking group.